Thomas Jefferson, landscape architect. Part IV: Washington

By now we know that the 45th president of the US is not somebody who is going to spend a whole lot of attention to the relation between state and landscape. Still, there remains much to learn from the landscape architect/president. The development of the nation’s capital shows how the versatility of landscape—unlike the firmness of architecture—allows for a unification of conflicting political ideals.

For 26 years of his life, Jefferson’s energies were devoted to promoting and perfecting the new capital. Repugnant as the evils of city life were to him, he must have made a great concession in his anti-urban philosophy to devote so much time to creating the national capital. During the summer of 1790—while George Washington was the first president—two issues paralysed Congress: the future location of the nation’s capital and the question of how America’s finances and debts should be handled, “two of the most irritating questions,” as Jefferson remarked. With great effort, spending years of careful politics, he managed to broker a deal combining the two, by exchanging the south’s acceptance to pay for a larger part of the debts, for a favourable location of the new capital: on the Potomac River along the Maryland and Virginia border, far away from the commercial and urban centres, and thus expressing the vision of the United States as an agrarian republic.

At that time, professional city planning had not yet emerged from the art of architecture and science of military engineering which had for centuries been responsible for the design of European cities. The city of Washington was the first attempt to plan a national capital for a democratic form of government on a site deliberately picked for that purpose. The design of the city was to express the government and its (lack of) power. Thus, Jefferson, as a Republican, wanted it to be unobtrusive, while the Federalist President Washington envisioned a grand an imposing city.

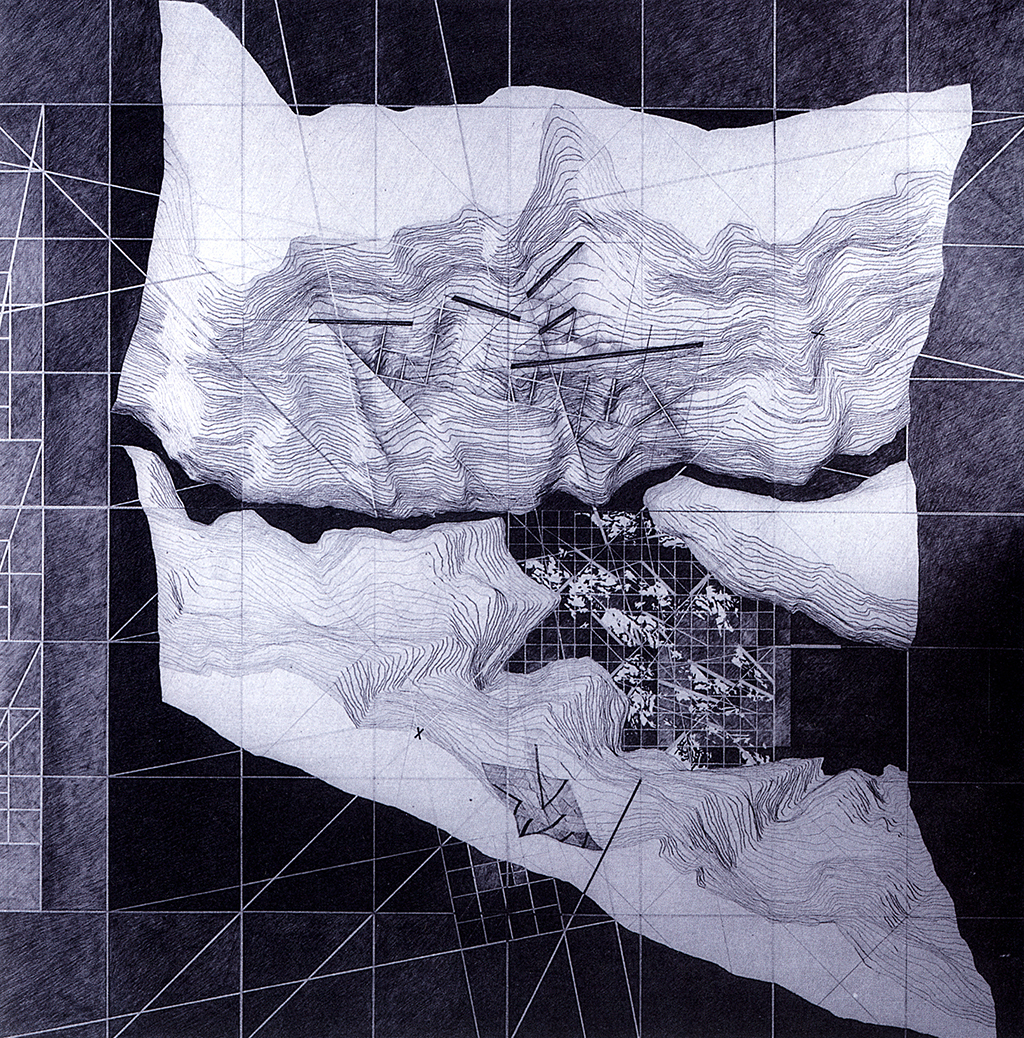

Jefferson’s first memorandum about the future capital stated that it should be laid out on a rectangular grid that would grow organically over time, spreading out from its centre. The city should be a city of gardens, interspersed with squares for public walks. He laid out the programme, specified as “a territory not exceeding 10. miles square to be located by metes and bounds. […] I should propose [the streets] to be at right angles & that no street be narrower than 100. feet, with foot-ways of 15. feet where a street is long & level.” Obviously, his conception of the future city was based on the conventional gridiron plan with which he was familiar. He wrote down precise rules and regulations, foreseeing almost every problem that would be encountered.

By contrast, the magnificent city that Washington and his chosen designer Charles L’Enfant dreamed up, would proclaim a mighty, dominant central government. The scheme that L’Enfant submitted, a radial plan superimposing the grid that Jefferson had proposed, was no other than André Le Nôtre’s design for the gardens of Versailles. However, a year later L’Enfant was fired, because of his stubborn refusal to submit to the authority of the commissioners, and Jefferson was left with the responsibility to complete the already accepted plan. With L’Enfant’s plan being so enormous that the city grew in small clusters around the important buildings instead of around a single centre, Jefferson’s improvement was to work on roads to link these separate areas.

Even before the first houses had been built, Jefferson had suggested lining the avenues and streets with trees—after all, a house could always be erected quicker than a tree would grow to maturity. Regarding tree-felling as “a crime little short of murder,” he also told the commissioners that people were not allowed to cut existing trees that he thought to keep for ornamental purposes for the city. But with no means to enforce this, by the time he became president, most trees were lost.

While Jefferson failed to stop Washington’s and L’Enfant’s grand plans, he managed to infuse them with his own ideals. Because of the capital’s remote location and the continuous lack of funds, for many years it wasn’t a bustling metropolis but remained a rural town, reflecting both the federalist ideals in its grand plan, and the republican ones in its atmosphere of a “very agreeable country residence … free from the noise, the heat, the stench & the bustle of a close built town.”

sources

Nichols, F.D. and Griswold, R.E. (1978) “The City of Washington” in: Thomas Jefferson, Landscape Architect. pp. 38-75.

Wulf, A. (2011) “City of Magnificent Intentions,” in: Founding Gardeners. The Revolutionary Generation, Nature, and the Shaping of the American Nation. pp. 124-153.